The Argentine mother who took on the Junta dictatorship over her 'disappeared' son

- Obtener vínculo

- X

- Correo electrónico

- Otras apps

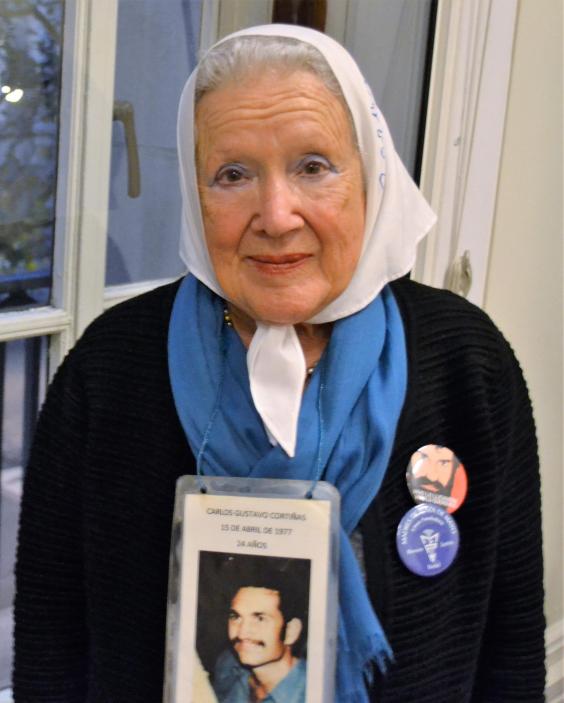

Every week Nora Cortiñas and her fellow Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo gathered outside the presidential palace, shaming the military dictatorship over the fate of their missing children

The housewife who became a global human rights heroin

She greets you within the grandeur of London University’s Senate House: 87 years old, tiny, but with the power to unsettle one of the most brutal military dictatorships the world has ever seen.

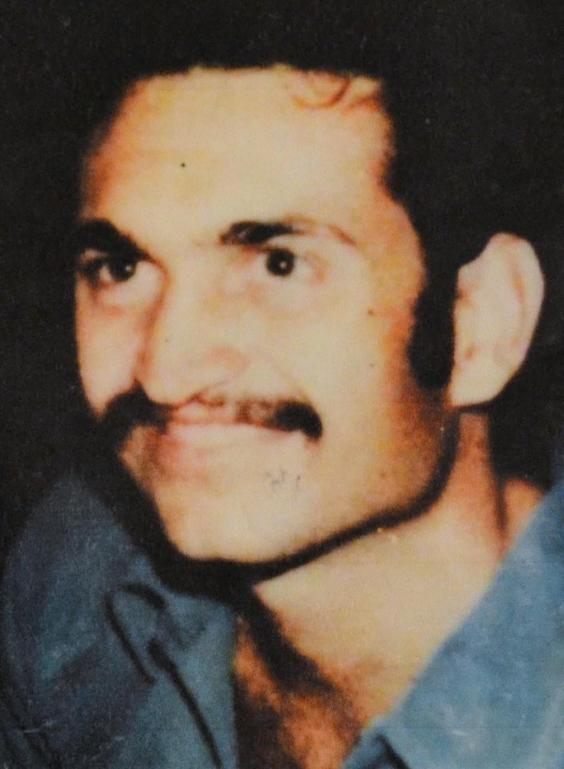

Nora Cortiñas still carries round her neck the laminated photo of her long-lost son, Carlos Gustavo Cortiñas, printed with the date he disappeared – 15 April 1977 – and her boy’s age when he was taken: 24.

She still insists on wearing the white headscarf that came to symbolise the defiance of Argentina’s Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo), through four long decades of demanding “memory, truth and justice” for their children.

Every week they stood opposite the presidential palace in the main square of Buenos Aires, demanding to know what the Junta had done to their sons and daughters, an unyielding rebuke to a dictatorship that thought state terror would stifle the merest whisper of dissent.

Forty years ago, Nora was a “traditional” Buenos Aires housewife, working from home as a dressmaker and teaching young girls to sew.

Then on a cold morning in April 1977, Gustavo said goodbye to his wife Ana and his two-year-old toddler Damian, set off for work, and was never seen by friends or family again.

“We never knew, we still don’t know to this day, exactly what happened to Gustavo,” says Nora. “We don’t know who kidnapped him. We don’t know where they took him. We don’t know how or when he was killed, or anything. Nada.”

Gustavo had become one of the desaparecidos: the “disappeared.” By the time Argentina’s military dictatorship ended in 1983, the disappeared would number some 30,000.

Gustavo had become one of the desaparecidos: the “disappeared.” By the time Argentina’s military dictatorship ended in 1983, the disappeared would number some 30,000.

The senior officers, who came to power in a military coup on 24 March 1976, had directed every branch of the state apparatus to root out “subversives”. Cruising the streets in dark green Ford Falcons, the death squads of the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (the AAA), would seize people and take them to secret detention centres, never to be seen again.

The forced disappearance tactic was likened to the ‘Night and Fog’ Decree issued by Adolf Hitler, to ensure that dissidents were not publicly executed, but instead made to vanish without trace.

The Nazis thought this would strike the maximum fear into anyone else contemplating dissent. The Argentine generals seemed to have the same idea. Six months after their coup, the disappearances were by some estimates running at an average rate of 30 a day.

Nora says Gustavo had never been violent – he was no longer even politically active by then. Instead, he was halfway through his university economics course and also working at the Ministry of Economy.

But years earlier, Gustavo had tried to improve the lot of the poor in the Villa 31 shanty town of Buenos Aires, working alongside Carlos Mugica, the Roman Catholic priest murdered by the AAA in May 1974.

He had once also been a supporter of the leftist Monteneros group – albeit without participating in its guerrilla activities. For a regime picking up people simply for being listed in an activist’s address book, this was more than enough.

Gustavo was seized at the train station on his morning commute, as Nora and her family realised when the military came looking for Ana.

“They interrogated her,” says Nora, “And every time Ana answered a question, the military would say ‘Yes, that coincides’, clearly indicating that Gustavo had been questioned.”

Mercifully, perhaps, they never took Ana or Damian.

Among the many horrors of what the Junta liked to call “The National Reorganisation Process”, the most shocking of all was how female detainees were robbed of their young children.

Days-old infants were taken from mothers. Women arrested while pregnant could find themselves giving birth blindfolded and tied by their hands and feet.

Then the baby they were never allowed to see would be taken and given to a “politically acceptable” couple, the better to prevent the rise of a new generation of “subversives”. The birth mother would nearly always be killed.

About 500 babies and infants were stolen by the dictatorship. Some were raised by the very men who had participated in the torture and murder of their parents, often never realising what their much-loved “father” had done, sometimes discovering only decades later.

“We never imagined that the repression could go to the lengths it did,” says Nora. “You can’t begin to imagine that you will never see your son or daughter again. So at the time of their kidnapping and even years later, we continued to look for our children alive.”

Now, though, Nora knows such hope is impossible.

Now, though, Nora knows such hope is impossible.

The prisoners were kept “hooded or blindfolded, forbidden to talk to one another, living in filth,” according to one account. “They were tortured, almost without exception, methodically, sadistically, sexually, with electric shocks and near-drownings and constant beatings, in the most humiliating possible way, not to discover information – very few had any information to give – but just to break them spiritually as well as physically, and to give pleasure to their torturers.”

The electric shocks would burn the prisoner’s flesh. As the trial of one Argentine officer prosecuted for crimes against humanity revealed in 2005, the torturers liked to call these sessions “barbecues”.

Some detainees were eventually put in front of firing squads. Others, though, were taken on “death flights”, drugged, stripped naked and flung out of aircraft at 4,000m (13,000ft) into the freezing waters of the South Atlantic.

Perhaps the worst secret detention centre was set up at the Naval Mechanical School in Buenos Aires. And yet, as Nora discovered while searching everywhere for news of her son, “there was even an office set up by the Navy supposedly to ‘provide information’ on the whereabouts of ‘missing people’, staffed by a Naval priest”.

She heard about the Mothers almost immediately after they first demonstrated outside the presidential palace on 30 April 1977.

Within days she had joined them, when they were still only 20-strong.

As they gathered every week in the Plaza de Mayo, coming to be identified by their white headscarves, the mothers’ every move was followed by the machine guns of soldiers posted on the rooftops around the square. In time, Nora and others would be called at home, threatened with jail, denounced as “terrorist mothers”.

A half-smile briefly passes across her lips: “We knew they were genocidal, but in a sense we weren’t afraid. The thought of finding our children was more important.

A half-smile briefly passes across her lips: “We knew they were genocidal, but in a sense we weren’t afraid. The thought of finding our children was more important.

“It was visceral – the love of our children, the desire to find them – you just had to do something.”

As word about the mothers spread nationally and then internationally, the military men, with their guns and the full apparatus of state terror at their disposal, were made to feel very uncomfortable by these awkward women.

“They did everything they possibly could,” says Nora.

But when a police officer told them they couldn’t stay where they were because gatherings of three or more people were forbidden, the mothers simply began walking round the square in pairs.

When the Junta tried to ridicule them as las locas (the crazy women), they refused to be shamed into silence. After all, as one of them later recalled: “Of course we were mad - mad with grief. They took a woman’s most precious gift: her child.”

Eventually, the dictatorship decided that the mothers of the disappeared must themselves disappear.

Eventually, the dictatorship decided that the mothers of the disappeared must themselves disappear.

In December 1977, they seized three of the group’s founding members – Azucena Villaflor, Esther Careaga and María Eugenia Bianco – along with two French nuns and seven other helpers.

Early in 1978, unidentified bodies began to wash up on the beaches south of Buenos Aires, before being hastily removed to mass graves by agents of the dictatorship.

The three mothers had been among the dead. Their injuries were consistent with being thrown into the sea from an aircraft.

And yet Nora and the others carried on. And no, she still wasn’t afraid.

“The love for our children was the only thing that was important,” says Nora. “It wasn’t an act of courage, like we were standing up to the repression or the fear around it. It was just … We had to find our children, and we had to find them alive.”

She adds: “That kind of suffering didn’t make us fearful, didn’t make us afraid, even when the mothers themselves were disappeared. In a sense it became the source of our courage and our capacity to continue to look for our children.”

You ask her to describe the pain of losing Gustavo. Even now, 40 years on, she has to bite her lip to stop the tears flowing. She chops at her arm with her hand.

“It’s like part of you has been amputated. There is no way to fully describe that pain, and it never goes away. The only way that pain could be brought to an end, the only way you could be made whole again, would be to find that loved one.”

And so even now, 34 years after democracy was restored in 1983, the mothers continue to meet in the Plaza de Mayo every Thursday at 3.30pm.

They do so partly because although democracy was restored and some secrets of the detention centres emerged, their victory was never complete. In 1989, for example, as part of his “reconciliation” policy, Carlos Menem granted presidential pardons that effectively released hundreds of officers who had been in jail for human rights abuses.

They do so partly because although democracy was restored and some secrets of the detention centres emerged, their victory was never complete. In 1989, for example, as part of his “reconciliation” policy, Carlos Menem granted presidential pardons that effectively released hundreds of officers who had been in jail for human rights abuses.

Not only does Nora still not know what happened to Gustavo, she fears some of those responsible will escape justice.

And in the case of Santiago Maldonado, an activist allegedly last seen alive being arrested at a protest for indigenous peoples’ rights in August, she sees the worrying, if much-disputed possibility that forced disappearances might not be a thing of Argentina’s past.

“Forced disappearance,” she warns, “Is the crime of all crimes. It cannot be left unpunished.”

Forty years after she started, her white headscarf is actually the latest in a succession of headscarves, worn out one by one.

Under the Junta, people were terrified of talking to the mothers, fearing they too would disappear.

Now their Thursday afternoon gatherings are often greeted with shouts from passer-by: “Mothers of the square, we embrace you.”

The world embraces them too, as Nora knows. For those further north, facing a new kind of politics in the form of Donald Trump, she advises: “You mustn’t be afraid to stand up for your ideals, to have principles, to stand in solidarity with others.”

Had he lived, Gustavo would be a 64-year-old grandfather. His toddler son Damian is now a 42-year-old father of two children.

For Nora, the gatherings of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo have gradually acquired a new significance.

“Our pain,” she explains, “made it possible for us to lift up the banners of the causes that our children struggled for, to take on their fight for social justice, for basic respect, and most importantly, the struggle that there should never again be forced disappearances.”

“My son Gustavo is not here,” she says, “but he is a path. I am fighting for him. I really want the seed that young people planted in this country to grow.”

Now a great-grandmother, her face lined by age, she stares directly at you.

“My name is Nora Irma Morales de Cortiñas, and I form part of the Mothers of the Plazo de Mayo founding line, and I am very proud of my children, and of all children who continue to struggle for their ideals.”

When you suggest her son Gustavo would be very proud of her, she covers her eyes. She doesn’t want to show her tears.

Nora Cortiñas still carries round her neck the laminated photo of her long-lost son, Carlos Gustavo Cortiñas, printed with the date he disappeared – 15 April 1977 – and her boy’s age when he was taken: 24.

She still insists on wearing the white headscarf that came to symbolise the defiance of Argentina’s Madres de Plaza de Mayo (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo), through four long decades of demanding “memory, truth and justice” for their children.

Every week they stood opposite the presidential palace in the main square of Buenos Aires, demanding to know what the Junta had done to their sons and daughters, an unyielding rebuke to a dictatorship that thought state terror would stifle the merest whisper of dissent.

Forty years ago, Nora was a “traditional” Buenos Aires housewife, working from home as a dressmaker and teaching young girls to sew.

Then on a cold morning in April 1977, Gustavo said goodbye to his wife Ana and his two-year-old toddler Damian, set off for work, and was never seen by friends or family again.

“We never knew, we still don’t know to this day, exactly what happened to Gustavo,” says Nora. “We don’t know who kidnapped him. We don’t know where they took him. We don’t know how or when he was killed, or anything. Nada.”

Gustavo Cortiñas was 24 when he was seized at the train station on his morning commute, never to return

The senior officers, who came to power in a military coup on 24 March 1976, had directed every branch of the state apparatus to root out “subversives”. Cruising the streets in dark green Ford Falcons, the death squads of the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (the AAA), would seize people and take them to secret detention centres, never to be seen again.

The forced disappearance tactic was likened to the ‘Night and Fog’ Decree issued by Adolf Hitler, to ensure that dissidents were not publicly executed, but instead made to vanish without trace.

The Nazis thought this would strike the maximum fear into anyone else contemplating dissent. The Argentine generals seemed to have the same idea. Six months after their coup, the disappearances were by some estimates running at an average rate of 30 a day.

Nora says Gustavo had never been violent – he was no longer even politically active by then. Instead, he was halfway through his university economics course and also working at the Ministry of Economy.

But years earlier, Gustavo had tried to improve the lot of the poor in the Villa 31 shanty town of Buenos Aires, working alongside Carlos Mugica, the Roman Catholic priest murdered by the AAA in May 1974.

He had once also been a supporter of the leftist Monteneros group – albeit without participating in its guerrilla activities. For a regime picking up people simply for being listed in an activist’s address book, this was more than enough.

Gustavo was seized at the train station on his morning commute, as Nora and her family realised when the military came looking for Ana.

“They interrogated her,” says Nora, “And every time Ana answered a question, the military would say ‘Yes, that coincides’, clearly indicating that Gustavo had been questioned.”

Mercifully, perhaps, they never took Ana or Damian.

Among the many horrors of what the Junta liked to call “The National Reorganisation Process”, the most shocking of all was how female detainees were robbed of their young children.

Days-old infants were taken from mothers. Women arrested while pregnant could find themselves giving birth blindfolded and tied by their hands and feet.

Then the baby they were never allowed to see would be taken and given to a “politically acceptable” couple, the better to prevent the rise of a new generation of “subversives”. The birth mother would nearly always be killed.

About 500 babies and infants were stolen by the dictatorship. Some were raised by the very men who had participated in the torture and murder of their parents, often never realising what their much-loved “father” had done, sometimes discovering only decades later.

“We never imagined that the repression could go to the lengths it did,” says Nora. “You can’t begin to imagine that you will never see your son or daughter again. So at the time of their kidnapping and even years later, we continued to look for our children alive.”

When Nora joined them, the mothers were only 20-strong, but their numbers soon swelled (AFP/Getty)

The prisoners were kept “hooded or blindfolded, forbidden to talk to one another, living in filth,” according to one account. “They were tortured, almost without exception, methodically, sadistically, sexually, with electric shocks and near-drownings and constant beatings, in the most humiliating possible way, not to discover information – very few had any information to give – but just to break them spiritually as well as physically, and to give pleasure to their torturers.”

The electric shocks would burn the prisoner’s flesh. As the trial of one Argentine officer prosecuted for crimes against humanity revealed in 2005, the torturers liked to call these sessions “barbecues”.

Some detainees were eventually put in front of firing squads. Others, though, were taken on “death flights”, drugged, stripped naked and flung out of aircraft at 4,000m (13,000ft) into the freezing waters of the South Atlantic.

Perhaps the worst secret detention centre was set up at the Naval Mechanical School in Buenos Aires. And yet, as Nora discovered while searching everywhere for news of her son, “there was even an office set up by the Navy supposedly to ‘provide information’ on the whereabouts of ‘missing people’, staffed by a Naval priest”.

She heard about the Mothers almost immediately after they first demonstrated outside the presidential palace on 30 April 1977.

Within days she had joined them, when they were still only 20-strong.

As they gathered every week in the Plaza de Mayo, coming to be identified by their white headscarves, the mothers’ every move was followed by the machine guns of soldiers posted on the rooftops around the square. In time, Nora and others would be called at home, threatened with jail, denounced as “terrorist mothers”.

The junta in 1977: Admiral Emilio Massera, President Jorge Videla and General Orlando Agosti (Getty)

“It was visceral – the love of our children, the desire to find them – you just had to do something.”

As word about the mothers spread nationally and then internationally, the military men, with their guns and the full apparatus of state terror at their disposal, were made to feel very uncomfortable by these awkward women.

“They did everything they possibly could,” says Nora.

But when a police officer told them they couldn’t stay where they were because gatherings of three or more people were forbidden, the mothers simply began walking round the square in pairs.

When the Junta tried to ridicule them as las locas (the crazy women), they refused to be shamed into silence. After all, as one of them later recalled: “Of course we were mad - mad with grief. They took a woman’s most precious gift: her child.”

The mothers in 1982. When they walked round the Plaza de Mayo, their every move was followed by armed troops on rooftops (AFP/Getty)

In December 1977, they seized three of the group’s founding members – Azucena Villaflor, Esther Careaga and María Eugenia Bianco – along with two French nuns and seven other helpers.

Early in 1978, unidentified bodies began to wash up on the beaches south of Buenos Aires, before being hastily removed to mass graves by agents of the dictatorship.

The three mothers had been among the dead. Their injuries were consistent with being thrown into the sea from an aircraft.

And yet Nora and the others carried on. And no, she still wasn’t afraid.

“The love for our children was the only thing that was important,” says Nora. “It wasn’t an act of courage, like we were standing up to the repression or the fear around it. It was just … We had to find our children, and we had to find them alive.”

She adds: “That kind of suffering didn’t make us fearful, didn’t make us afraid, even when the mothers themselves were disappeared. In a sense it became the source of our courage and our capacity to continue to look for our children.”

You ask her to describe the pain of losing Gustavo. Even now, 40 years on, she has to bite her lip to stop the tears flowing. She chops at her arm with her hand.

“It’s like part of you has been amputated. There is no way to fully describe that pain, and it never goes away. The only way that pain could be brought to an end, the only way you could be made whole again, would be to find that loved one.”

And so even now, 34 years after democracy was restored in 1983, the mothers continue to meet in the Plaza de Mayo every Thursday at 3.30pm.

The mothers still gather weekly, to protest ongoing social injustices and the release of some of the officers responsible (Getty)

Not only does Nora still not know what happened to Gustavo, she fears some of those responsible will escape justice.

And in the case of Santiago Maldonado, an activist allegedly last seen alive being arrested at a protest for indigenous peoples’ rights in August, she sees the worrying, if much-disputed possibility that forced disappearances might not be a thing of Argentina’s past.

“Forced disappearance,” she warns, “Is the crime of all crimes. It cannot be left unpunished.”

Forty years after she started, her white headscarf is actually the latest in a succession of headscarves, worn out one by one.

Under the Junta, people were terrified of talking to the mothers, fearing they too would disappear.

The world embraces them too, as Nora knows. For those further north, facing a new kind of politics in the form of Donald Trump, she advises: “You mustn’t be afraid to stand up for your ideals, to have principles, to stand in solidarity with others.”

Had he lived, Gustavo would be a 64-year-old grandfather. His toddler son Damian is now a 42-year-old father of two children.

After 40 years, Nora Cortiñas still does not know what happened to her 24-year-old son (Tom Goulding)

“Our pain,” she explains, “made it possible for us to lift up the banners of the causes that our children struggled for, to take on their fight for social justice, for basic respect, and most importantly, the struggle that there should never again be forced disappearances.”

“My son Gustavo is not here,” she says, “but he is a path. I am fighting for him. I really want the seed that young people planted in this country to grow.”

Now a great-grandmother, her face lined by age, she stares directly at you.

“My name is Nora Irma Morales de Cortiñas, and I form part of the Mothers of the Plazo de Mayo founding line, and I am very proud of my children, and of all children who continue to struggle for their ideals.”

When you suggest her son Gustavo would be very proud of her, she covers her eyes. She doesn’t want to show her tears.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario