JAPON- WOMEN's POWER

For women at the Olympics, more coverage doesn't equal respectful coverage

An exclusive look at the #RespectHerGame report shows women Olympians are 10 times more likely to be visually objectified than men.

Hello, and welcome to Power Plays, a no-bullshit newsletter about sexism, etc., in sports, written by me, Lindsay Gibbs.

I hope you all are enjoying/surviving the Tokyo Olympics — this time difference is absolutely brutal, and I still don’t think this Olympics (or, really, any Olympics) should be happening, but I’ve been glued to my television and 4:00 a.m. streams nonetheless.

As most of you know, here at Power Plays, we have an ongoing #CoveringtheCoverage series, which aims to hold the media accountable for its coverage of women’s sports. Usually, our series focuses in on newspaper coverage, since that’s easiest to tally with such a limited team. So, as you can imagine, I was absolutely thrilled when The Representation Project reached out to offer Power Plays an exclusive first look the #RespectHerGame report, which looks at representations of gender in media coverage during the first week of the Tokyo Olympics.

Not only is it really amazing to be able to look at detailed breakdowns of television coverage which was analyzed by fancy algorithms and six researchers, but it’s particularly valuable to be able to get this data almost in real time, while the Olympics are still ongoing.

Here’s a trailer for the project, which includes some of the sexist coverage in past Olympics that inspired this project, and that I recommend only watching if you want your blood to boil.

And here are the biggest takeaways from the #RespectHerGame report:

Women got more overall coverage: Athletes in women’s sports received a staggering 59.1% of screen time in primetime Olympic coverage.

But men overwhelmingly control their stories: Men make up 82% of live Olympic commentators.

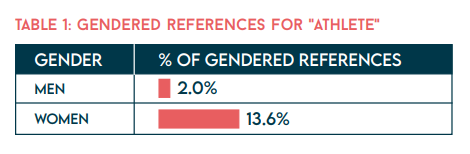

Men’s sports is still viewed as the default: Athletes in men’s sports are referred to as “male [athlete|sport]” just two percent of the time, while athletes in women’s sports are given the “female” qualifier 13.6% of the time.

Women are more exposed and sexualized than their male counterparts: Athletes in women’s sports wear revealing outfits in competition more than their male counterparts (69.9% compared to 53.5%), and are 10 times more likely to be objectified by camera angles (5.7% compared with 0.6%).

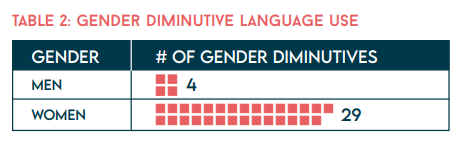

Women are still infantilized: Athletes in women’s sports are seven times more likely to be referred to using gender diminutive language (such as “girl” or “lady” or “chick”) as their counterpart in men’s sports.

The #RespectHerGame report focused on NBC primetime coverage during the first week of the Olympics — you know, those heavily-produced nightly shows hosted by Mike Tirico that NBC puts the most muscle (read: money) behind.

Overall, they analyzed 1,052 Olympic competitors (81.7%), commentators (13.2%), reporters/interviewers (4.6%), and non-competing interviewees (0.5%) in 24 hours of primetime Olympic coverage during the first week of the games (from Saturday, July 24th - Friday, July 30th).

Here is a link to their full report, but keep reading below for the Power Plays breakdown.

Okay, friends. Let’s do this.

This report offers legitimate proof that progress is being made, which is worth celebrating!

Before we dive deeply into the depressing statistics here, I do want to take a minute to highlight the good news in this report. Because it is there, I promise!

I mean, it’s absolutely huge that women’s sports got almost 60% of primetime coverage. Less than 20 years ago, at the 2002 Olympics, men’s sports received twice as much coverage as women’s sports. But since then, women’s sports has been dominating Olympic coverage. By the London Olympics in 2012, women were receiving 55% of primetime coverage, and in 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, that number rose to 58%.

Considering that women’s sports in general receive around four percent of all media coverage, these numbers are monumental, and it’s only a matter of time before executives at media organizations across the world stop being blissfully, defiantly obtuse and realize that women’s sports can drive ratings and make them money outside of the Olympics, too. (Seriously, they have to get it soon, right?!)

And according to this report, primetime Olympic coverage has made some significant strides when talking about athletes in women’s sports. #RespectHerGame found that commentators only spoke directly about the physical appearance of athletes 2.9% of the time for men and 2.5% of the time for women, and that no athletes were sexually objectified by commentary. Meanwhile, only two athletes were the subject of body shaming by a commentator, one woman and one man.

Additionally, the report found no difference between men’s sports and women’s sports in terms of how commentators discussed romantic partners, marital status, or parenting. This is a *huge* step forward from the 2012 London Olympics when, according to the #RespectHerGame report, “fastest” and “strongest” were the most common words used to describe athletes in men’s sports, compared to “married” or “unmarried” for women.

Hold the good news tightly, friends. Cherish it.

Unfortunately, women are still being excluded from the commentary booth, and commentary about women athletes is still seeping with sexism.

Despite the fact that primetime Olympic coverage predominantly features athletes in women’s sports and attracts a large female audience, the broadcast still suffers from a “by men, for men” bias.

First off, it looked at the genders of people who are holding the mics during the primetime broadcasts, and found that NBC is still following the sports-media trope of pigeon-holing women as sideline reporters and hosts, while allowing men to provide the actual commentary and analysis. During the first week of coverage, the majority of reporters who interviewed athletes after their events were women (54.2%), while the vast majority of commentators were men (82.0%). That means that most of the stories people are watching are framed by and told by men.

Perhaps that’s one reason why the language used to talk about women’s sports remains subpar.

The #RespectHerGame report found that athletes in women’s sports are referred to as “female [sport here]” 13.6% of the time compared to only two percent of the time for athletes in men’s sports, which reinforces the idea that men’s sports are the default, while women’s sports are “other.”

The report also looked at what it referred to as “gender diminutive language,” words that serve to infantilize or demean women. It found that athletes in women’s sports are seven times more likely to be referred to using a gender diminutive.

The most prolific diminutive used for men was “boy,” with four total mentions during primetime Olympic coverage. Meanwhile, the most prolific gender diminutives for women was “girl” (21 mentions), “lady” six mentions), and “chick” (two mentions).

(Friends, it’s 2021 and “chick” is still being used on a primetime broadcast? I am channeling A’ja Wilson’s side-eye.)

Frankly, none of this is acceptable.

“We know representation matters, so we were disappointed to see that 80% of the hosts and commentators in prime-time were men, When it’s still men who overwhelmingly tell women’s stories and men who decide how women’s accomplishments will be framed, it shouldn’t come as a surprise when sexist patterns stay entrenched,” said Caroline Heldman, executive director of the Representation Project.

“Our report shows that coverage repeatedly diminished women as merely ‘female’ athletes rather than ‘real’ ones and belittled some of the most accomplished athletes in the world as ‘girls’ or as ’chicks’. It’s time to get talented women journalists off the literal sidelines and let them make real change.”

Women’s bodies are still being over-sexualized, too.

In the previous section, we broke down the “by men” part of the problem. Now let’s talk about the “for men” clause. Essentially, it means that the people governing and broadcasting women’s sports are still making too many decisions with the straight male gaze in mind.

Now, it’s common for athletes of all genders to wear tight, revealing clothing for competitive reasons, but frequently, uniform guidelines force the issue. This was highlighted earlier this summer, when the Norwegian beach handball team was fined for wearing shorts instead of bikini bottoms in the European Beach Handball Championships. (It’s important to note that beach handball is not an Olympic sport, and that contrary to widespread belief, there are uniform options for women’s beach volleyball players other than bikinis.) In Tokyo, the German gymnastics team bucked tradition and wore unitards with long pant legs, as opposed to the strandard bikini-cut leotard, noting they were tired of “sexualization.”

The #RespectHerGame study found that athletes in women’s sports are more likely to be shown in revealing outfits than those in men’s sports (69.6% compared with 53.5%). This isn’t a problem if all competitors are wearing uniforms they are comfortable in, but it is an issue if the decision is out of their hands, and if the media exploits their bodies. And, unfortunately, it seems like the latter is happening.

This is the most disturbing statistic of the report for me: Women athletes are about ten times more likely to be visually objectified than men athletes, 5.7% compared with 0.6%. The study defines visual objectification as “when a camera pans an athlete’s body and/or focuses on specific body parts in a sexualizing way.”

“While there was some improvement in how women were talked about, our study reveals that women are ten times more likely than men to be sexualized on camera. This kind of objectification is dehumanizing and dangerous,” said Jennifer Siebel Newsom, the founder and chief creative officer of the Representation Project.

“And it’s only made worse by the infuriating fact that Olympic Committee officials mandate that women wear uniforms that are more revealing than competitors would often choose or that competition requires. This is intolerable and has to change. Let women choose what they wear and let's ensure the media gives these exceptional athletes the respect they deserve.”

How do we put a stop to this nonsense once and for all?

Just a we can be happy for the medalists and devastated for the fourth-place finisher in Olympic competitions, we can look at the findings of this report and feel both invigorated by the progress and frustrated by the persistent sexism.

But predominantly, this report has left me fired up to keep pushing for change and #CoveringtheCoverage, because I truly believe that holding the media accountable for its coverage choices is the quickest and most effective way to achieve a more equitable sports media ecosystem.

The #RespectHerGame report offers a few actionable items, which I am just going to copy below because I think they hit the nail on the head:

Action steps for media executives:

Hire and feature more women commentators.

Direct camera people to avoid sexualizing women athletes with camera angles.

Direct commentators to use “athlete” when referring to men and women athletes instead of gendering the term.

Direct commentators to avoid referring to women athletes as “girls,” “ladies,” or “chicks”

Action steps for Olympic executives:

Allow women, men, and gender non-conforming athletes to wear the clothing of their choice (instead of mandating sexually revealing outfits for women competitors)

These steps are about a basic as it gets, but would make a huge difference if implemented.

However, I also want to stress that it’s not a enough to look at coverage solely from a binary gender perspective. Going forward, studies need to account for different races, nationalities, gender identities, gender presentations, sexual preferences, and more, because everyone deserves coverage that respects their identities and intersections.

(On that note, here’s a good piece by Britni de la Cretaz about how Olympic commentators weren’t prepared to use the proper pronouns for nonbinary athletes.)

We’re going to keep doing the work here at Power Plays; if you have any ideas for #CoveringtheCoverage projects, or have studies of your own in this vein you would like to amplify, please don’t hesitate to reach out. (lindsay@powerplays.news.)

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario