Being a sitter for Egon Schiel

Being a sitter for Egon Schiele,By Sophie Haydock

With their direct eye contact and powerful stances, Egon Schiele’s drawings of women were some of the first to recognise female autonomy. But who were the artist’s models and how did their relationships with Schiele play out on paper?

-

From the Winter 2018 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. Please note, this article contains some adult content.

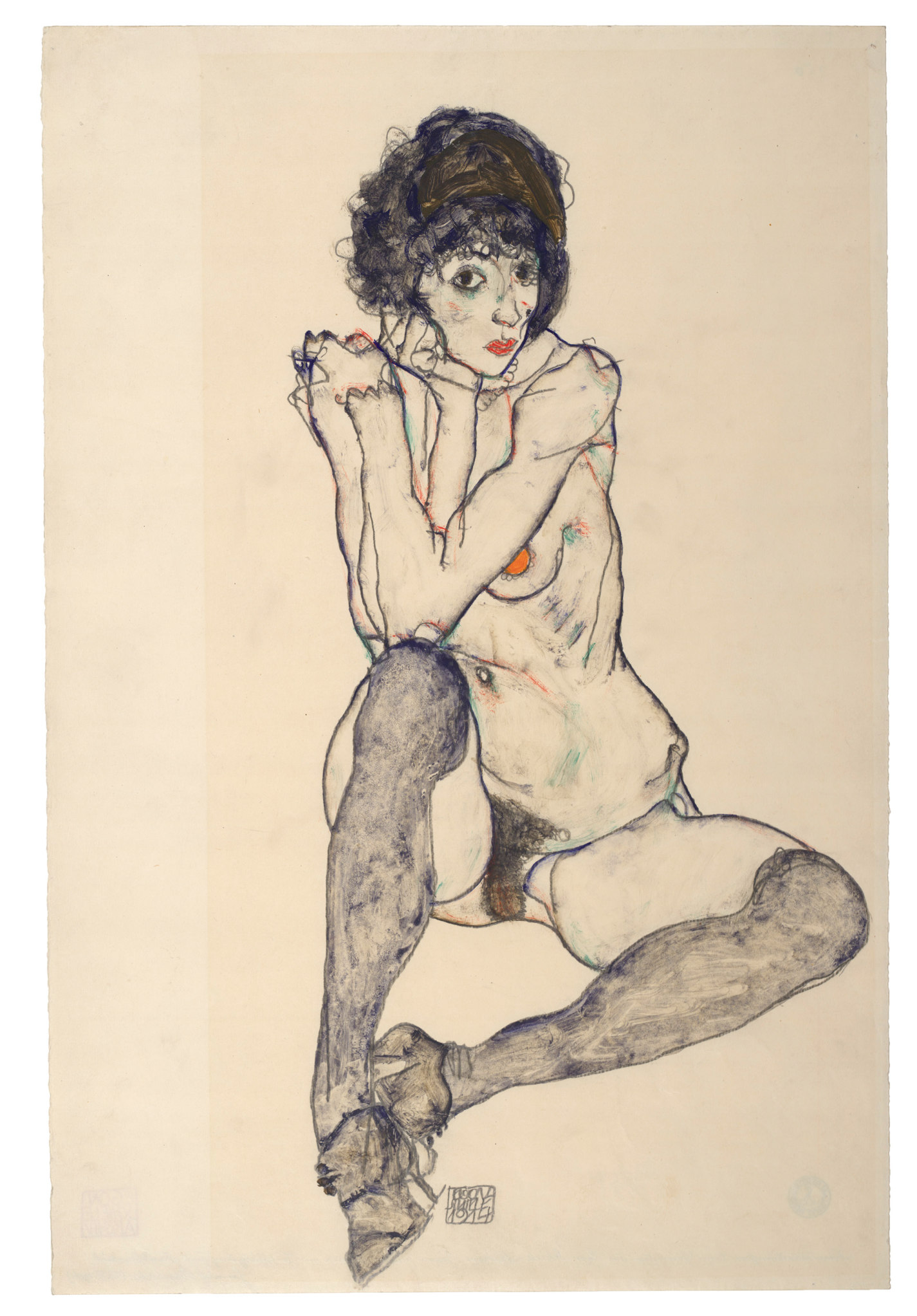

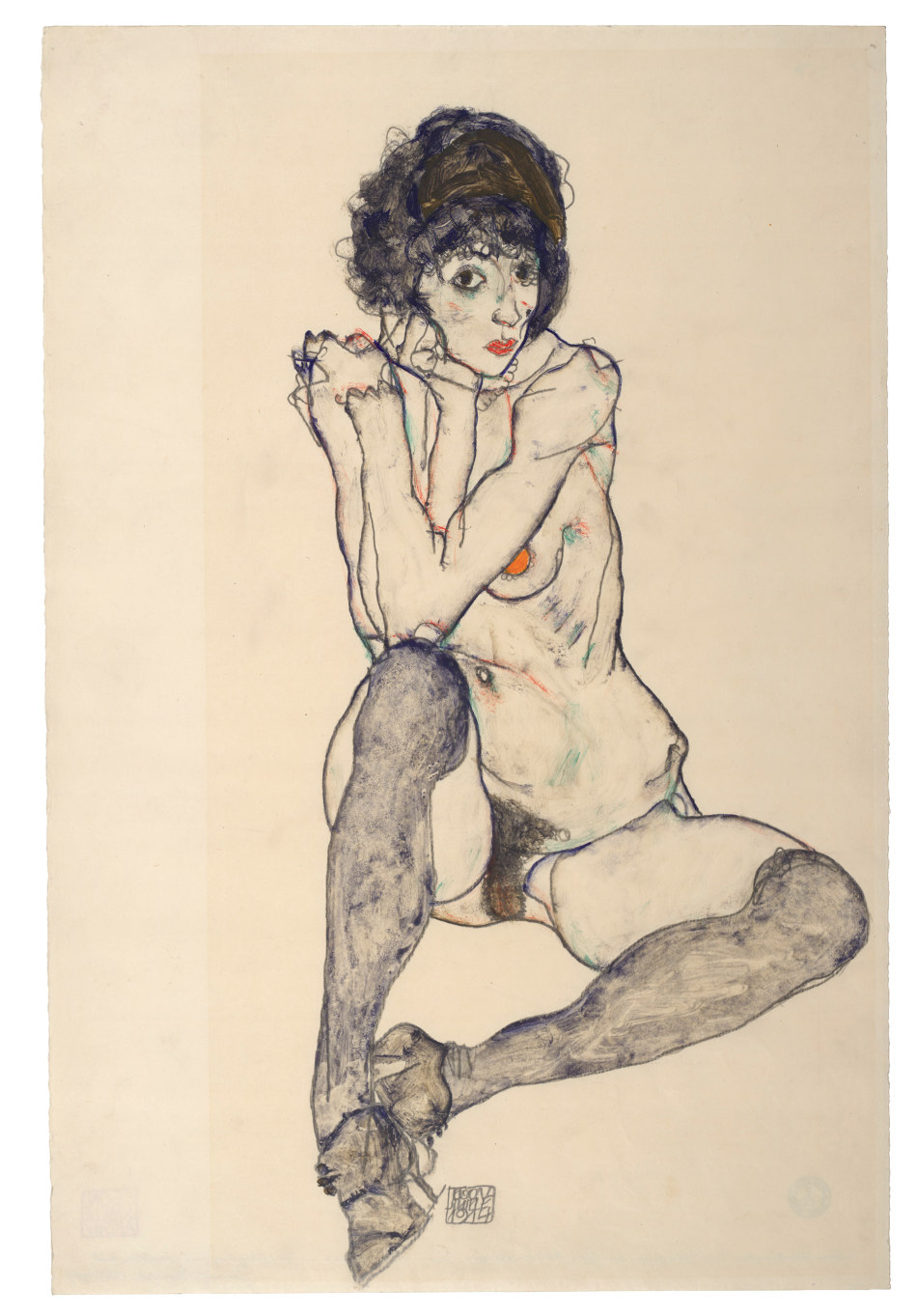

Breasts. A nipple. Pale-brown paper sketched with angular hips, pouting lips, open legs. The viewer’s gaze flashes from exposed vagina to sultry, penetrating eyes. She shows us everything. But we don’t know her name. And yet the look of this black-haired model, as seen in Seated Female Nude, Elbows Resting on Right Knee (1914), still transcends the century between our moment and the one when she walked into 24-year-old Egon Schiele’s studio, removed her clothes and took up that unforgettable pose. What was going through her mind in the hours that she sat for the young artist?

Schiele is recognised as one of art’s great provocateurs. But a question still lingers about the price paid by the mostly young, lower-class models who both posed for him and fuelled his dazzling success. There are many female faces to observe in the current exhibition in the RA’s Sackler Wing, but few of them are named, with the exception of those who were closest to the artist: Schiele’s stern and unhappy mother, Marie; his sister Gertrude, one of the artist’s earliest life models; his wife, Edith, and her older sister, Adele.

-

Egon Schiele, Seated Female Nude, Elbows Resting on Right Knee, 1914.

Egon Schiele, Seated Female Nude, Elbows Resting on Right Knee, 1914.

Pencil and gouache on Japan paper. 48 x 32 cm. The Albertina Museum, Vienna.

-

Many of Schiele’s models are only identifiable by their hair colour: the slender, stocking-clad redhead; the pair of black-haired girls; the blonde with the beaded necklace (Seated Female Nude, 1912). “You can see in works from 1910-12 Schiele’s feelings of confusion and fear,” says Jane Kallir, author of the Egon Schiele catalogue raisonné and co-director of Galerie St Etienne in New York – few people in the world know Schiele’s artwork as intimately as she does. “There’s a push-pull between him and these women, as to who is really in charge,” she continues. “Who is the subject and who is the object?”

But in fact, starting around 1912, we are able to single out one of those women in his artwork – the beguiling, blue-eyed Walburga (Wally) Neuzil. It is believed that it was Schiele’s friend and mentor, Gustav Klimt, who in early 1911 introduced Schiele to the 17-year-old model. Wally came from a poor, provincial background and worked in Vienna as an artist’s model, then considered a lowly profession tantamount to prostitution. It is rumoured that Wally first modelled for, and may have been in a relationship with, Klimt. Such a theory has never been proven but, if true, it reveals how models were passed between artists, almost as commodities. Wally became Schiele’s lover and muse and inspired some of his greatest work, including the haunting Portrait of Wally Neuzil (1912; not in show), painted in oil. Here, she is elevated beyond passive model – the look in her eyes seems to challenge both viewer and artist.

-

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Wally Neuzil, 1912.

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Wally Neuzil, 1912.

© Leopold Museum.

-

Although Wally kept her own apartment, she quickly became Schiele’s constant companion. When the artist left Vienna for his mother’s hometown of Český Krumlov (now Krumau) in 1911, Wally accompanied him. And when Schiele was forced to leave the picturesque Renaissance town after the locals objected to his unconventional lifestyle, which included living with a woman he was not married to, Wally followed him again, this time to Neulengbach. There, once more, the artist’s way of life angered the town’s inhabitants – only this time, he ended up in prison.

Schiele spent 24 days alone in a holding cell. He was charged with kidnapping, statutory rape and public immorality, after one of the town’s children, a 13-year-old girl, Tatjana von Mossig, ran away from home and sought refuge in Schiele’s studio. The first two charges were quickly dropped. Schiele, however, was convicted of the third, after the police found many ‘obscene’ drawings and alleged that the young teenagers he regularly used as models would have seen them. Wally stood by Schiele through the ordeal, visiting him at the prison and bringing him the vibrant orange fruit that can be seen in a watercolour, Single Orange Was the Only Light (not in show), painted on 19 April 1912. But despite the intensity of their relationship, Wally was Schiele’s mistress, never truly viewed by the artist as his equal. He was not prepared to marry her. “He was always going to do what was expected of his class,” explains Kallir. Schiele even made Wally sign a statement that she was not in love with him.

After the harrowing experience of prison, Schiele’s priorities changed. He returned to Vienna, and in 1915, while still living with Wally, proposed to the bourgeois girl-across-the-street Edith Harms. His choice can be interpreted as a calculated decision – a way to climb the social ladder. Edith said yes, and Wally was let go but not entirely discarded. An indication of how little Schiele understood women, and how he brazenly tried to control them to fulfil his own needs, is clear in an agreement Schiele presented to Wally, promising that the pair would spend two weeks away together each summer. Wally refused and never saw him again. Shortly after, she joined the Red Cross as a nurse, but died of scarlet fever in a military hospital in what is now Croatia, at the end of 1917.

Schiele’s wife Edith didn’t fair much better in his all-consuming orbit. In her diary she wrote about her husband: “Nowhere do I find understanding, and this hurts me so.” It’s fair to suppose that, given her upbringing, she would have been uncomfortable taking up the explicit poses that he needed. Schiele drew Edith masturbating, mirroring sketches made by Klimt in 1904 and 1912–13.

-

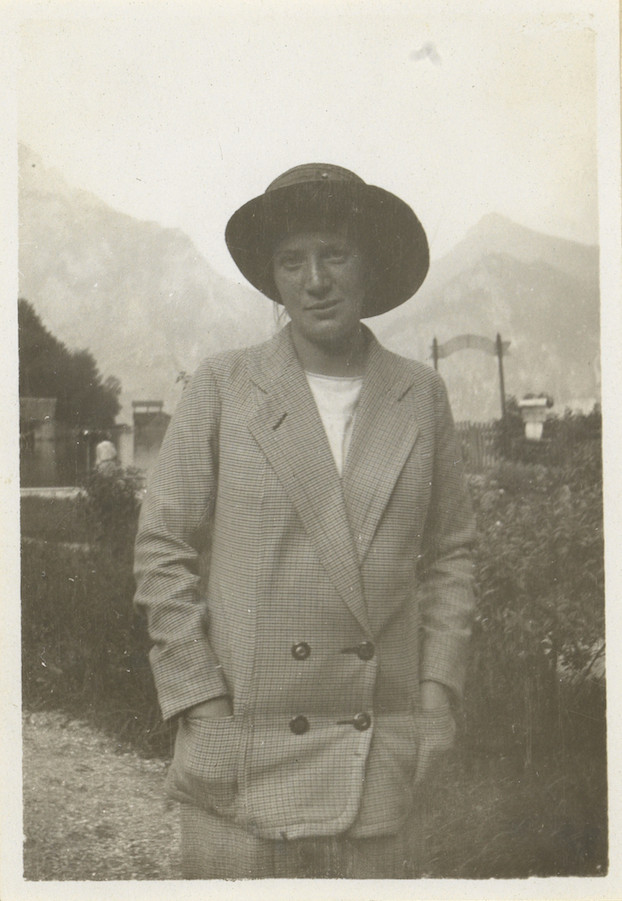

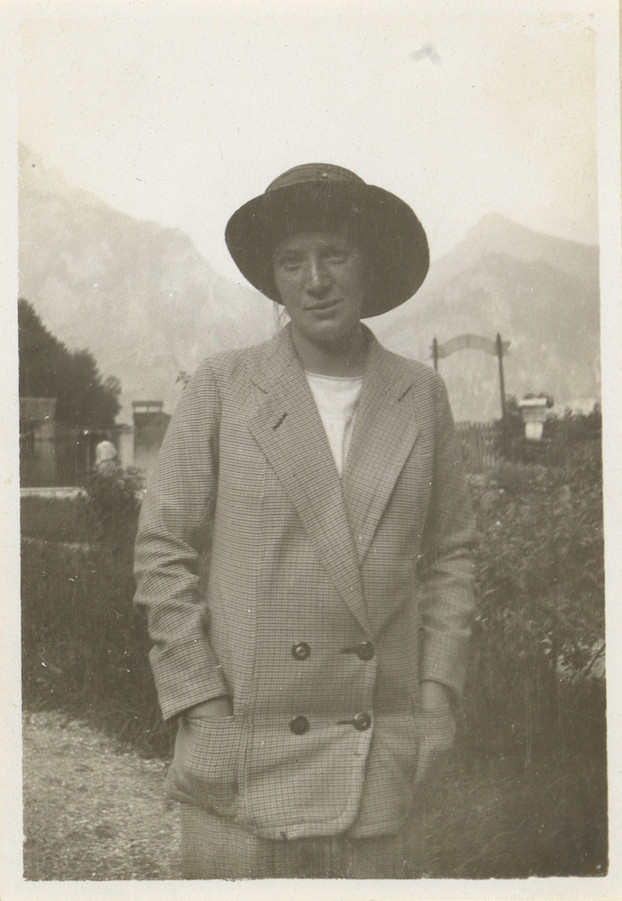

Wally Neuzil at Lake Traunsee, Vienna, 1913

Wien Museum

-

The criticism that has hounded Egon Schiele accuses him of producing ‘pornographic’ artworks. The art historian and curator Alessandra Comini points to a line in the sand that is still being fought over: “Pornography”, she says, “is meant to stimulate someone else. Eroticism is the documentation of what makes us tingle. It also lies in the eyes of the beholder, does it not?” This sentiment echoes the words of Schiele himself during his trial at Neulengbach: “I do not deny that I have made drawings and watercolours of an erotic nature. But they are always works of art. Are there no artists who have made erotic pictures?” For this reason, Comini does not believe Schiele’s works can be considered pornographic. “Sexually explicit, perhaps,” she says. “But it’s your choice to look at them. And your choice what you choose to see in them.” Comini continues to observe compassion in his work: “You would have to choose not to see the tenderness Schiele has for the women who sit for him.”

It’s true that, much like his contemporaries and, as a young artist of limited means, Schiele tapped into a stream of prostitutes and destitute women to model for him. But Kallir says that questioning whether Schiele respected his models is “too much of a 21st-century concept”. She adds: “These women were not his equals; that was simply not on the cards.” The Austrian artist was the product of a very different time – Vienna at the turn of the 20th century was a period when women were especially limited by class and marital status.

And yet Schiele consistently defied the norms of his era. He played with the concept of gender in his art, often adopting poses for his self-portraits that were considered feminine. He also depicted his female subjects with degrees of emotional depth and verve that had rarely been seen before. This was at a time when Schiele’s contemporaries were avidly treating women like objects for their own satisfaction. For example, Schiele’s rival Oskar Kokoschka had a life-size doll made of his former partner Alma Mahler to remember her by after she broke up with him. “The Western artistic tradition of the female nude was developed by men for men,” Kallir points out. “It’s a tradition that tries to suppress and neutralise female sexuality and turn it into something safe for men to look at.” Schiele’s nudes, she adds, crucially, are not safe. Kallir goes on to say male oppression is often born of fear and insecurity: “What’s unusual about Schiele is that rather than trying to hide his fear and insecurity, he openly acknowledges it.”

Schiele sparked a shift in the representation of masculinity and femininity and paved the way for a more gender-fluid approach for the artists and sitters who came after him. “Schiele possessed a forthright recognition of female sexual autonomy,” says Kallir. “Before Schiele, you don’t see many women in Western art who own their sexuality in the same way.” Kallir points out the confident power stances – squared shoulders, direct eye contact and unflinching awareness of their own physical appeal – adopted by many of his female models. “Schiele had a more humanistic appreciation of women’s intelligence and personalities than most male artists.”

Whether you love him or loathe him, deem him to be a pioneer or pornographer, it’s clear that the women who sat for Schiele, resulting in some of his most profound artworks, were at times dismissed, downtrodden and discarded. But, ultimately, they were also elevated and admired in ways that had rarely been seen before. As viewers, let’s not forget the human hearts that lie behind the layers of pencil and paint; the women whose names we know – among them Gertrude Schiele, Wally Neuzil, Edith and Adele Harms – and those whose identities have been lost to history, but who, exceptionally, and without voice, speak to us today.

-

Sophie Haydock is a freelance journalist, currently writing a novel about the women in Schiele’s life.

Klimt / Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna The Sackler Wing, Royal Academy, until 3 February 2019. Exhibition organised by the Royal Academy and the Albertina Museum, Vienna. Booking is essential.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario